Note

This post is the first one in a series dedicated to my workflow: which are the tools and methods I use when I have to write anything.

- Why I always write in pure text

- Writing in pure text: Choose a markup language (WIP)

- Building process: Let’s play with make

As you might know, a huge part of my daily activities as a finance professor involve writing, in a way or another: writing emails, preparing slides or handouts, reporting, coding and obviously, blogging. I also maintain a “lab journal” in which I report everyday what I did, and how I did it [1].

I must confess that I mostly write on a computer, and my handwriting actually became barely readable along the years. This is a bit sad, but using the computer to write also has many advantages, especially in terms of efficiency.

What I explained so far is so common that your situation is probably the same, whoever you are: students, colleagues, friends, or someone of my family. Even you, the accidental wanderer who arrived on this page by pure chance, probably share the same kind of habits when it comes to writing something. And yes, writing is ubiquitous in our world of endless reporting, messaging and emailing.

What are probably less common are the tools and methods I use to produce written content. Most people use specialized software, like Microsoft Word for handouts, articles and reports, Microsoft Powerpoint for slides, etc. Note that the reason I cite these products instead of competitors is that actually, it is now really difficult to find anyone using other pieces of software for these tasks. There are indeed many problems related to this de facto monopoly — but that is another story, which had been told many times already. Instead of complaining about that, I only want to introduce an alternative, that I and many others happily use every day.

Note that an important point that I want to make here is that alternatives exist: no, you are not condemned for life to use Word and Powerpoint if you don’t want to. You have choice, and I think it is important to consider all possibilities before making a choice. And you have choice even if you work in an environment in which everyone uses the Microsoft monsters.

Enough for an introduction which is way longer than I expected already. As the title of this post implies, I want to explain here why I write nearly everything in “pure text”, that is, something which you can read and edit with a text editor such as Notepad on Windows.

Writing in pure text have many advantages which I would never trade now for anything else.

Text is light and standard

First of all, a pure text file is light, far lighter than a Word or Powepoint file. The full source of a 250 pages finance textbook we wrote with colleagues years ag, is 690 Ko, yes, less than one megabyte for a 250 pages book. I know that storage is cheap these days, but bandwidth is not as cheap, and being able to send any text by email without worrying about file size limit on your provider’s side, or the cost of your data subscription, is a real comfort.

In addition, text files follow standards and are thus “understandable” everywhere, by all machines and operating systems. This is a huge advantage when you work with people in heterogeneous environment: I use Linux on my laptop, most of my colleagues use some more or less recent version of Windows, and students usually prefer Apple machines and systems. Colleagues and students don’t even know I use a different system, and actually cannot notice it when I send them a document.

Choices

Another advantage, really important to me, is choice. When you work with text, you have a lot of choices about the tools you use, first for editing the text file, and then to “compile” it, that is, get the final (probably pdf) result.

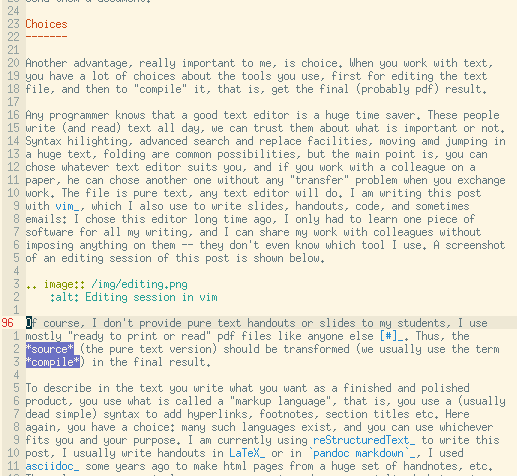

Any programmer knows that a good text editor is a huge time saver. These people write (and read) text all day, we can trust them about what is important or not. Syntax hilighting, advanced search and replace facilities, moving amd jumping in a huge text, folding are common possibilities, but the main point is, you can chose whatever text editor suits you, and if you work with a colleague on a paper, he can chose another one without any “transfer” problem when you exchange work. The file is pure text, any text editor will do. I am writing this post with vim, which I also use to write slides, handouts, code, and sometimes emails: I chose this editor long time ago, I only had to learn one piece of software for all my writing, and I can share my work with colleagues without imposing anything on them — they don’t even know which tool I use. A screenshot of an editing session of this post is shown below.

Of course, I don’t provide pure text handouts or slides to my students, I use mostly “ready to print or read” pdf files like anyone else [2]. Thus, the source (the pure text version) should be transformed (we usually use the term compile) in the final result.

To describe in the text you write what you want as a finished and polished product, you use what is called a “markup language”, that is, you use a (usually dead simple) syntax to add hyperlinks, footnotes, section titles etc. Here again, you have a choice: many such languages exist, and you can use whichever fits you and your purpose. I am currently using reStructuredText to write this post, I usually write handouts in LaTeX or in pandoc markdown, I used asciidoc some years ago to make html pages from a huge set of handnotes, etc. These languages are simple, some are generic and some specialized, but again, you can chose whatever you want.

History and version control

Finally, pure text files are easy to version and diff. “Diffing” means to list the differences between different versions of the same text. This is done by specialized programs, which allow you to keep the history of your text, all successive versions, simply by storing the consecutive differences. The program can then rebuild any version for you from the set of differences. That means that whenever you want, you can access previous versions, know by whom and when was introduced a given change, and more. And all this without cluttering your hard disk (remember, text is light, and anyway you only store differences), and blazingly fast. Once you try it, you never want to come back. It is incredibly useful to be able to come back to any point in time, whether you are working alone or in collaboration.

To be continued

Stay tuned for the next post about my workflow: what are the markup languages I use and prefer, and why.

In the meanwhile, may I suggest you have a look at Jeff Leek’s very opinionated post, The future of education is plain text ?

| [1] | See for example http://colinpurrington.com/tips/lab-notebooks about lab notebooks and why it might be a good idea to maintain one even if you are not working in a lab. |

| [2] | Even if you use Word to produce a document, it is probably better and safer to convert it to pdf before sending it to anyone: chances are greater that the layout you spent so many hours to craft carefully is not completely messed up by their Word version, which is very likely different from yours. |